Filters

The Filter class can be used to generate, manipulate and save filter banks and transfer functions. Filters are represented internally as Signal and come in three flavours: finite impulse responses, impulse responses, and transfer functions, set by the fir attribute, which takes a string (‘FIR’, ‘IR’, or ‘TF’). FIR filters are applied using scipy.signal.filtfilt(), which avoids group delays and is intended for highpass and lowpass filters and the like. IR filters are applied using scipy.signal.fftconvolve() and are intended for long room impulse responses, binaural impulse responses and the like, where group delays are intended. TF filters do not contain impulse response taps, but gains per frequency bin, making it easy to construct complicated filters.

Simple Filters

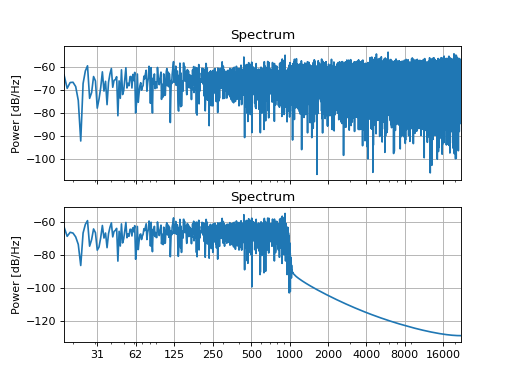

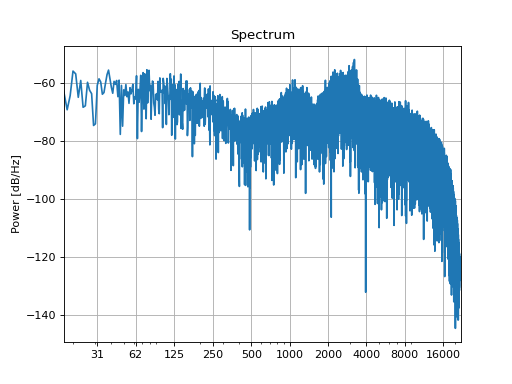

Simple low-, high-, bandpass, and bandstop filters can be used to suppress selected frequency bands in a sound. For example, if you don’t want the sound to contain power above 1 kHz, apply a 1 kHz lowpass filter:

from matplotlib import pyplot as plt

sound = slab.Sound.whitenoise()

filt = slab.Filter.band(frequency=1000, kind='lp')

sound_filt = filt.apply(sound)

_, [ax1, ax2] = plt.subplots(2, sharex=True)

sound.spectrum(axis=ax1)

sound_filt.spectrum(axis=ax2)

(Source code, png, hires.png, pdf)

The filter() of the Sound class wraps around Filter.cutoff_filter() and Filter.apply() so that you can use these filters conveniently from within the Sound class.

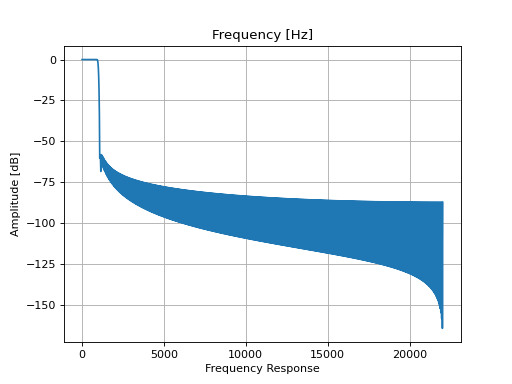

Filter design is tricky and it is good practice to plot and inspect the transfer function of the filter:

filt.tf()

(Source code, png, hires.png, pdf)

Inspecting the waveform of the sound (using the waveform() method) or the rms level (using the slab.Sound/level attribute) shows that the amplitude of the filtered signal is smaller than that of the original, because the filter has removed power. You might be tempted to correct this difference by increasing the level of the filtered sound, but this is not recommended because the perception of intensity (loudness) depends non-linearly on the frequency content of the sound.

Filter banks

A Filter objects can hold multiple channels, just like a Sound object. In the following, we will refer

to filters with multiple channels as filter banks. You can create filter banks the same way you create multi-channel

sound (since the Filter and Sound class both inherit from the parent Signal class).

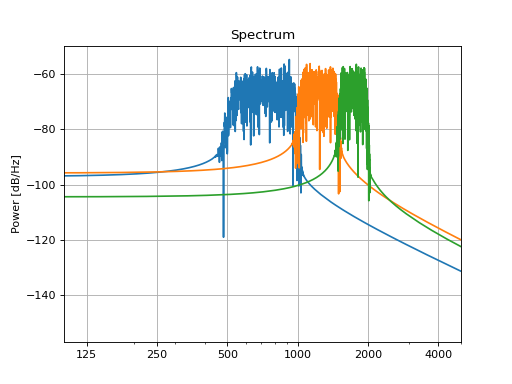

When you apply a filter bank to a single sound, each filter will be applied to a separate copy of the sound and the

apply() function will return a sound with a number of channels equal to the number of filters in the bank.

This way you can create, for example, a series of sounds with different frequency bands:

filters = []

low_cutoff_freqs = [500, 1000, 1500]

high_cutoff_freqs = [1000, 1500, 2000]

for low, high in zip(low_cutoff_freqs, high_cutoff_freqs):

filters.append(slab.Filter.band(frequency=(low, high), kind='bp'))

fbank = slab.Filter(filters) # put the list into a single filter object

sound_filt = fbank.apply(sound) # apply each filter to a copy of sound

# plot the spectra, each color represents one channel of the filtered sound

_, ax = plt.subplots(1)

sound_filt.spectrum(axis=ax, show=False)

ax.set_xlim(100, 5000)

plt.show()

(Source code, png, hires.png, pdf)

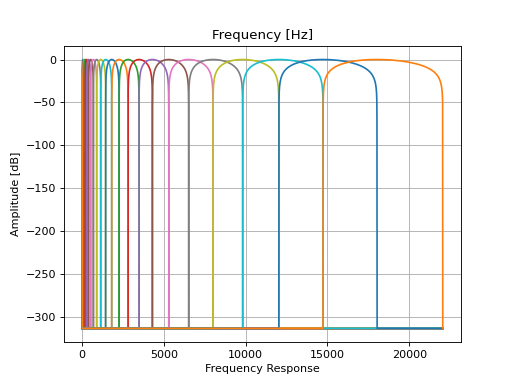

The channels, or subbands, of the filtered sound can be modified and re-combine with the combine_subbands()

method. An example of this process is the vocoder implementation in the Sound class, which uses these features

of the Filter class. The multi-channel filter is generated with cos_filterbank(), which produces

cosine-shaped filters that divide the sound into small frequency bands which are spaced in a way that mimics the

filters of the human auditory periphery (equivalent rectangular bandwidth, ERB). Here is an example of the transfer functions of this filter bank:

fbank = slab.Filter.cos_filterbank()

fbank.tf()

(Source code, png, hires.png, pdf)

A speech signal is filtered with this bank, and the envelopes of the subbands are computed using the

envelope() method of the Signal class. The envelopes are filled with noise, and the

subbands are collapsed back into one sound. This removes most spectral information but retains temporal information

in a speech signal and sound a bit like whispered speech. Here are the essential bits of code from the

vocode() method to illustrate the use of a filter bank. The first line records a speech sample

from the microphone (say something!):

signal = slab.Sound.record() # record a 1 s speech sample from the microphone

fbank = slab.Filter.cos_filterbank(length=signal.n_samples) # make the filter bank

subbands = fbank.apply(signal) # get a sound channel for each filter channel

envs = subbands.envelope() # now get the envelope of each frequency band...

noise = slab.Sound.whitenoise()

subbands_noise = fbank.apply(noise)

subbands_noise *= envs # ... and fill them with noise

subbands_noise.level = subbands.level # keep subband level of original

vocoded = slab.Filter.collapse_subbands(subbands_noise, filter_bank=fbank)

vocoded.play()

If you want to apply multiple filters to the same sound in sequence without creating subbands, you can simply use a for loop. For example, you could remove different parts of the spectrum using bandstop filters:

sound = slab.Sound.whitenoise()

# create a filter bank which consists of three separate bandstop filters

filter_bank = slab.Filter([slab.Filter.band(kind="bs", frequency=f) for f in [(200, 300), (500, 600), (800, 900)]])

for i in range(filter_bank.n_channels):

sound = filter_bank.channel(i).apply(sound)

If the a one-channel filter is applied to a multi-channel sound, the filter will be applied to each

channel individually. This can be used, for example, to easily pre-process a set of recordings (where

every recordings is represented by a channel in the slab.Sound object). If a multi-channel filter

is applied to a multi-channel signal with the same number of channels each filter channel is applied to

the corresponding signal channel. This mechanism is used, for example, during the equalization of a set of loudspeakers.

Equalization

In Psychoacoustic experiments, we are often interested in the effect of a specific feature. One could,

for example, take the bandpass filtered sounds from the example above and investigate how well listeners

can discriminate them from a noisy background - a typical cocktail-party task. However, if the transfer

function of the loudspeakers or headphones used in the experiment is not flat, the findings will be biased.

Imagine that the headphones used were bad at transmitting frequencies below 1000 Hz. This would make a sound

with center frequency of 550 Hz harder to detect than one with a center frequency of 1550 Hz. To prevent this from

happening, we have to equalize the headphones’ transfer function. You can measure the

transfer function of your system by playing a wide-band sound, like a chirp, and recording it with a probe microphone

(which itself must have a flat transfer function). From this recording, you can calculate the transfer function, which

is basically the difference in the power spectrum of the played sound and the recording. We can take the opposite of

that difference to create an inverse filter. Apply the inverse filter to a sound before playing it through that system

to compensate for the uneven transfer, because the inverse filter and the actual transfer function cancel each other.

The equalizing_filterbank() method does most of this work for you. For a demonstration,

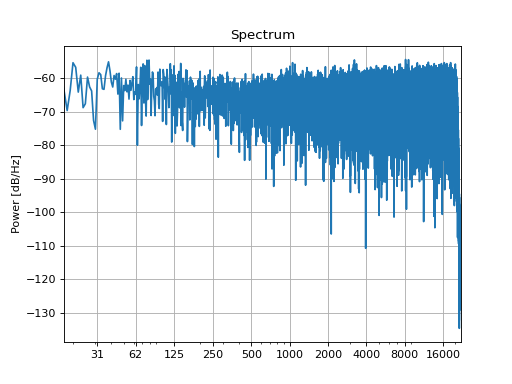

we simulate a (pretty bad) loudspeaker transfer function by applying a random filter:

import random

freqs = [f * 400 for f in range(10)]

gain = [random.random()+.4 for _ in range(10)]

tf = slab.Filter.band(frequency=freqs, gain=gain)

sound = slab.Sound.whitenoise()

recording = tf.apply(sound)

recording.spectrum()

(Source code, png, hires.png, pdf)

With the original sound and the simulated recording we can compute an inverse filter und pre-filter the sound (or in this case, just filter the recording) to achieve a nearly flat playback through our simulated bad loudspeaker:

inverse = slab.Filter.equalizing_filterbank(reference=sound, sound=recording)

equalized = inverse.apply(recording)

equalized.spectrum()

(Source code, png, hires.png, pdf)

If there are multiple channels in your recording (assembled from recordings of the same white noise through several

loudspeakers, for instance) then the equalizing_filterbank() method returns a filter bank with one

inverse filter for each signal channel, which you can apply() just as in the example above.